The sky over Tromsø was the wrong color for February.

Instead of the deep, dry blue that usually hangs over the frozen harbor, a soft, almost springlike haze sat low on the water. The thermometer outside the fish warehouse read +3°C. A pair of eiders paddled lazily through water that should have been locked under solid ice.

On the pier, marine biologist Kari Johansen watched a gull snatch an early-emerging cod worm from the surface and shook her head. “This is all happening a month too soon,” she muttered.

And the wildlife that depends on winter doesn’t know the rules anymore.

Early February and an Arctic that feels… broken

Ask any veteran meteorologist watching the polar charts this year and you’ll hear the same uneasy word: “breakdown.”

That classic, tight whirl of polar cold that usually locks over the Arctic in early February is wobbling, splitting, leaking warmth northward like a cracked bowl.

Weather models show pulses of subtropical air surging toward the pole, pushing temperatures up to 20°C above normal in some places. Sea ice that should be thickening is thinning. Snowpacks are crusted with rain and then refrozen into icy armor.

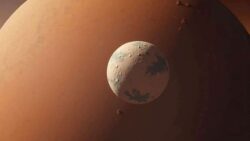

From space, satellites see strange shapes where the ice should be clean and solid. On the ground, the anomalies have feathers and fur and fins.

On a small island off Svalbard, a research camera caught a female polar bear pacing an exposed, dark shoreline in late January.

She should have been hunting seals on stable pack ice, storing fat for the long lean months ahead. Instead, rain had pounded the snow into slick ice, and the sea surface remained worryingly open, full of broken floes pushed around by stormy winds.

Scientists reviewing the footage later noticed something else: seabirds in the background, already pairing, weeks earlier than usual. Arctic foxes had been spotted hunting on bare rock where snow denning sites used to sit.

Nothing seemed catastrophic in a single frame. But stretched across the whole region, those small mis-timed moments start to look like the early edges of a biological cliff.

The phrase researchers are quietly using now is “phenological tipping point” – the point where seasonal timing comes so far out of sync that whole food webs snap.

Arctic life has evolved around an almost clockwork schedule: sea ice freeze, spring melt, plankton bloom, fish feeding frenzy, birds nesting, pups and chicks arriving.

When February behaves like late March, everything shifts. Plankton might bloom in ice-free water before fish larvae are ready. Seal pups could be born on unstable ice that cracks beneath them. Caribou may migrate and calve based on day length, only to find that the plants they rely on have already sprouted and withered in a heatwave.

One warm February doesn’t cause that collapse by itself. A string of them might.

How an early Arctic breakdown pushes wildlife toward a tipping point

For meteorologists, the alarm bells ring first in the upper atmosphere.

A sudden warming event in the stratosphere can disrupt the polar vortex – that tight ring of winds that usually keeps Arctic air bottled up. When that ring weakens or splits, chaotic patterns ripple down to the weather we feel.

This winter, forecast maps show something that used to be rare becoming almost routine: jagged tongues of warmth invading the Arctic Ocean while lobes of cold spill into North America or Europe.

On the ground, that means rain where snow should fall, thaw followed by flash-freeze, coastal storm surges chewing away at fragile permafrost shores.

For us, it’s weird weather. For Arctic animals, it’s a survival test they didn’t evolve for.

Take reindeer and caribou. Herds across Scandinavia and Russia have been hit by episodes locals now call “rain-on-snow disasters.”

A warm spell brings rain onto snow-covered tundra. When the temperature drops again, that water freezes into a hard ice layer. Reindeer hooves, evolved to scrape through powder to reach lichens, simply can’t punch through the crust.

In 2013 and again in 2020, tens of thousands of reindeer starved in northern Russia after such events. Herders remember finding animals alive but too weak to stand, surrounded by untouched food trapped under glassy ice.

Those were once-in-decades episodes. As February warms and swings between thaw and freeze more often, the “disaster” risks becoming the new normal.

The same timing trap hits smaller, less iconic creatures. Lemmings, for instance, depend on a fluffy subnivean world: that cozy, ventilated layer of snow at ground level where they tunnel, feed and breed through winter.

When mid-winter rains collapse that space into heavy, wet ice, lemmings lose their refuge. Predators like Arctic foxes then lose their main winter food source. The impact climbs up the chain: snowy owls skip breeding in years when lemming numbers crash.

Scientists tracking these cascading changes speak less about smooth, gradual warming now and more about thresholds. Once snow structure, sea ice stability, and seasonal timing cross certain lines, ecosystems can flip into new, poorer states.

*That’s what people mean by a biological tipping point – not a single dramatic moment, but a line you realize you’ve crossed only when the old patterns don’t come back.*

What can be done when February feels like April?

Faced with a global system problem, many people freeze. The Arctic feels far away, too big, too abstract.

Yet some of the most effective responses are surprisingly concrete and local – and already under way in the north.

Researchers and Indigenous communities are teaming up to track early-season changes with a level of detail satellites can’t touch. Hunters log when sea ice becomes unsafe. Fishers record odd spawning dates. Villages report rain-on-snow events in near real time via apps and radio.

These observations help agencies time emergency feedings for reindeer, adjust protected areas for seabirds, or alter fishing seasons to avoid hitting stressed populations right during those badly timed warm pulses.

It’s not glamorous. It’s field notes, phone calls, and community science – and it buys wildlife time.

For readers far from the Arctic, the question quietly lurking is: “So what do I actually do with this?”

We’ve all been there, that moment when another climate headline scrolls by and feels both terrifying and completely out of reach.

Let’s be honest: nobody really rewires their entire life after a single article.

Yet small, consistent shifts in how we vote, travel, heat our homes, and eat add up, especially in countries whose emissions still drive these polar disruptions.

Climate researchers increasingly point to three leverage points for ordinary people: backing strong climate policy, cutting high-impact emissions (think flights, big vehicles, wasted energy), and supporting organizations that protect and restore ecosystems. The Arctic tipping point isn’t just a polar bear story. It’s a mirror for the speed and scale of choices made far to the south.

“Every time February in the Arctic starts looking like late March, we’re testing the limits of what these ecosystems can absorb,” says Dr. Michael Richardson, a climatologist who has studied polar weather for two decades. “The scary part is that wildlife doesn’t get to negotiate. It either adapts fast enough, or it disappears from that place.”

- Watch the signals, not just the stories

Follow sea-ice and temperature anomaly maps from trusted sources so headlines have context. - Back Arctic-informed policy

Support leaders and laws that treat polar change as a global risk, not a niche environmental issue. - Protect timing, not just species

Push for fisheries, tourism, and shipping rules that respect breeding and migration windows now under stress. - Support local knowledge

- Cut personal high-carbon habits first, not last

A fragile season that belongs to all of us

Stand on an Arctic shoreline in early February and you feel something that never quite shows up in the graphs: a season out of character.

Waves where there should be a silent, creaking ice sheet. Damp air where your breath should sting. Bird calls that sound like they’ve skipped ahead in time.

Scientists talk about jet streams, thermal gradients, phenology curves. Elders speak instead of “winter losing its backbone.” Both are describing the same unease – a sense that we’ve pushed a once-stable system to the edge of what it can juggle.

The biological tipping point people fear is not a single, cinematic crash. It’s a slow, lopsided shift in who can still live there, who can’t, and what kind of Arctic our grandchildren will inherit through headlines and history books.

The breakdown of a February that used to be reliable is a warning shot the whole planet can hear, if we’re willing to listen and talk about what it asks of us now.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Early Arctic “breakdown” | Polar vortex disruptions and warm air intrusions are making February feel more like late March in many Arctic regions | Helps connect strange winter weather at home to large-scale shifts happening at the pole |

| Wildlife timing crisis | Rain-on-snow events, unstable sea ice and mistimed food peaks are pushing species toward a biological tipping point | Makes the climate story tangible through real impacts on animals and food webs |

| Actionable responses | Community monitoring, stronger climate policy, and lifestyle shifts targeting high emissions | Offers concrete ways to engage, rather than just absorbing alarming news |

FAQ:

- Question 1What exactly do meteorologists mean by an “Arctic breakdown” in early February?

They’re talking about a pattern where the normally stable cold pool over the Arctic gets disrupted, allowing warm air to surge north and cold air to spill south, scrambling usual seasonal conditions.- Question 2How does an early warm spell threaten a “biological tipping point” for wildlife?

Many Arctic species time breeding, migration and feeding to tight seasonal windows; repeated early thaws can push these timings so far out of sync that populations start collapsing instead of recovering.- Question 3Is this just about polar bears, or does it affect other animals too?

It affects whole ecosystems: reindeer, caribou, lemmings, seabirds, seals, fish, and the predators and people who depend on them.- Question 4Are these changes permanent, or could the Arctic “snap back” if emissions fall?

Some shifts, like lost sea ice and damaged permafrost coasts, are hard to reverse, but cutting emissions quickly can still stabilize the system and avoid deeper, more dangerous tipping points.- Question 5What can an individual realistically do about something happening so far away?

You can back strong climate policy, cut high-carbon habits, support Arctic science and Indigenous organizations, and keep this story in public conversation so it doesn’t fade into background noise.