In a modest house on the edge of town, the lights stay on thanks to something most of us throw away without a second thought.

For nearly a decade, a tech enthusiast has quietly run his home on hundreds of discarded laptop batteries, turning forgotten e‑waste into a surprisingly robust power system and cutting his reliance on the traditional grid.

From scrap pile to power plant

The project began back in November 2016, when the man, a fan of energy self-sufficiency, was already experimenting with solar panels and an old forklift battery. He wanted more storage, but new lithium batteries were far too expensive.

So he looked at what he already knew: laptops. Modern laptop batteries use lithium-ion cells, often with several still in good condition when the computer is scrapped. Bit by bit, he started rescuing them from recycling centres, repair shops and online listings.

“I started collecting them and now I have more than 650,” he says. “I’ve basically built my own power bank for the house.”

Over time, that collection grew past 1,000 used laptop batteries. Instead of ending up in landfill, many of those cells now store solar energy for his family’s daily life.

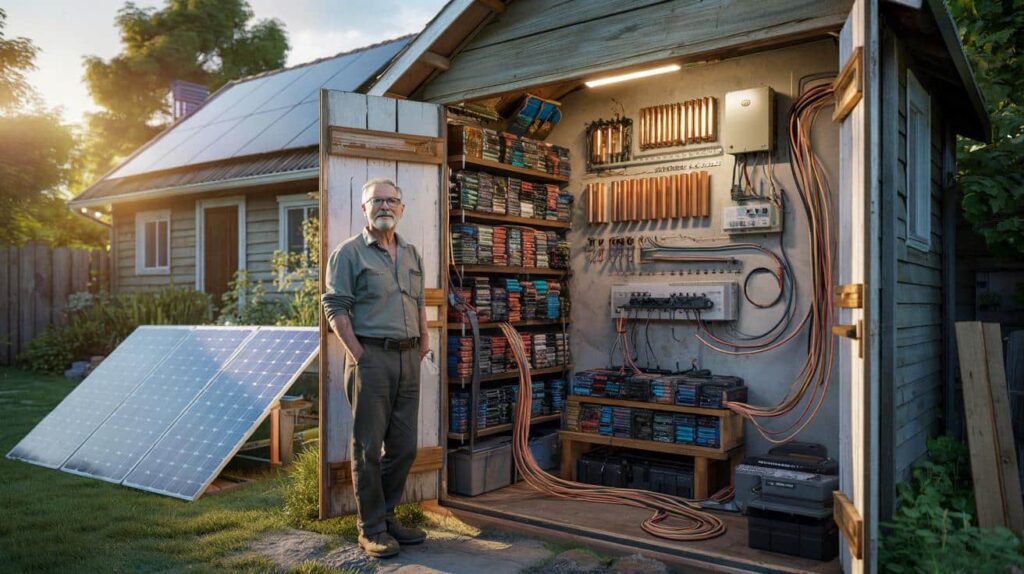

A shed that hides a homemade battery farm

The heart of the system is not inside the home at all, but in a separate shed roughly 50 metres away. That distance is deliberate. Lithium batteries can fail dangerously if mistreated, and keeping the installation away from bedrooms and living areas adds a layer of safety.

Inside the shed, shelves are lined with packs built from salvaged cells. Solar panels on the property feed chargers and controllers, which in turn send energy into these homemade battery banks. An inverter converts the stored direct current into alternating current compatible with normal household appliances.

He began by assembling packs of around 100 ampere-hours (Ah) each. Dozens of these packs are then wired together to form a larger storage system. Heavy copper cables handle the current flow between packs, chargers and the inverter.

The system has been running for almost ten years without fires or swollen batteries, a track record he attributes to careful sorting and conservative settings.

How the system is put together

- Solar panels mounted on the roof and shed feed charge controllers.

- Controllers charge banks of repurposed laptop cells grouped into 100 Ah packs.

- Copper cabling links the packs into a larger battery bank.

- An inverter supplies the house with 230/120 V AC power.

- Monitoring equipment tracks voltage, temperature and charge levels.

The setup might look messy to an outsider, but every pack is labelled, tested and wired with fuses. Failures do happen, he admits, yet the design allows individual packs to be isolated and replaced without shutting down the entire system.

The hidden potential of old laptop batteries

Most laptop battery packs contain several cylindrical lithium-ion cells. When a laptop “battery” is reported dead, that often means just one or two cells have failed, dragging down the whole pack. The rest can still hold a decent charge.

By opening the plastic casing and testing each cell, the user recovers the good ones and discards those that no longer meet basic capacity or safety standards. It is slow work: each cell must be charged, discharged and checked.

| Cell state | What he does with it |

|---|---|

| Good capacity, stable voltage | Goes into a house battery pack |

| Reduced capacity, but safe | Used in low-demand projects or backup lights |

| Unstable, swollen or damaged | Sent to proper recycling facility |

This patient sorting is what lets him claim years of operation without major incidents. He avoids pushing the cells to their technical limits. Packs are charged and discharged within a comfortable range to extend lifespan and reduce stress.

Ten years of home life on second-hand power

Today, much of his home’s electricity comes from this patchwork energy store. Daytime sun charges the batteries; evenings draw from the stored energy. The system supports lights, computers, and many domestic appliances.

He still keeps a link to the grid, partly as backup and partly for periods of bad weather, but bills have dropped sharply. Fluctuations in energy prices now concern him far less than his neighbours.

He sees the installation as both a technical challenge and a form of quiet protest against waste and rising energy costs.

The batteries have already lived one life inside laptops. Their second life, stacked in that shed, stretches into years of extra service before final recycling.

Costs, time and real-world constraints

Financially, the project leans on a mix of free and low-cost parts. Many laptop batteries came at no cost, exchanged for the promise of proper end-of-life handling. Others were bought in bulk as defective lots at a fraction of their original price.

Still, the system is not free. Solar panels, inverters, charge controllers, monitoring tools, fuses and copper cables all add up. The biggest investment, though, is time. Testing hundreds of cells, building packs and maintaining the system requires patience and basic electronics skills.

He does not claim this as a ready-made solution for everyone, but as proof that a different path is possible with the right knowledge and caution.

Safety, regulations and real risks

Lithium-ion batteries can be dangerous if mishandled. Short circuits, poor wiring or overheating can trigger fires. The builder of this system tries to limit those risks through spacing, ventilation and generous use of fuses and disconnect switches.

The shed location reduces impact in case something goes badly wrong. Sensors monitor temperatures and voltages. Packs showing strange behaviour are removed early rather than nursed along.

Anyone tempted to copy this approach faces regulatory questions too. In some countries, home-built battery banks fall into grey areas of electrical rules and insurance policies. If a fire did occur, insurers might investigate whether the system met any recognised standard.

Second-life batteries as a growing trend

While this project focuses on laptops, the same idea is starting to scale up with electric car batteries. When a car battery loses a chunk of its original capacity, it becomes less useful on the road but can still serve well in static storage.

Major energy companies and carmakers are already piloting “second-life” storage projects, where used EV batteries stabilise local grids or store solar energy for buildings. The home experiment in that quiet shed sits on the same continuum, just on a far smaller, more personal scale.

What this means for ordinary households

Most people will never build a 650-battery shed, yet the story highlights several trends that touch everyday life. Energy storage is becoming central to how homes use electricity, especially with rooftop solar.

New home battery systems, sold as plug-and-play products, follow safer, certified designs but rely on the same basic chemistry as the cells in a laptop. As prices fall, more households will consider pairing solar panels with storage, even if they never touch a soldering iron.

For those curious about doing more than just buying a unit, this kind of project also raises practical questions:

- Where does your old tech actually go when you recycle it?

- Could community repair cafés or makerspaces host safer, shared storage projects?

- What rules should guide the reuse of cells to balance creativity and safety?

Key concepts behind the project

A few terms help make sense of what is going on in that shed. “Ampere-hour” (Ah) measures how much charge a battery can deliver over time. A 100 Ah pack, for example, can ideally provide 10 amps for 10 hours. Combine many packs and you get a large energy reservoir.

The inverter is another crucial piece. Batteries store direct current (DC), while homes run on alternating current (AC). The inverter performs this translation, and its capacity limits how many devices can run at once.

The idea of “depth of discharge” also matters. Draining batteries fully shortens their lifespan. By cycling them only between, say, 20% and 80% charge, the builder sacrifices some capacity but gains years of use, which is vital when working with cells that have already lived one life.

All of this shows how a patchwork of old components, handled thoughtfully, can reshape a single home’s energy story. Between the shelves of cells, the hum of the inverter and the line of solar panels outside, that story adds a small but tangible chapter to the broader shift toward reuse and decentralised power.