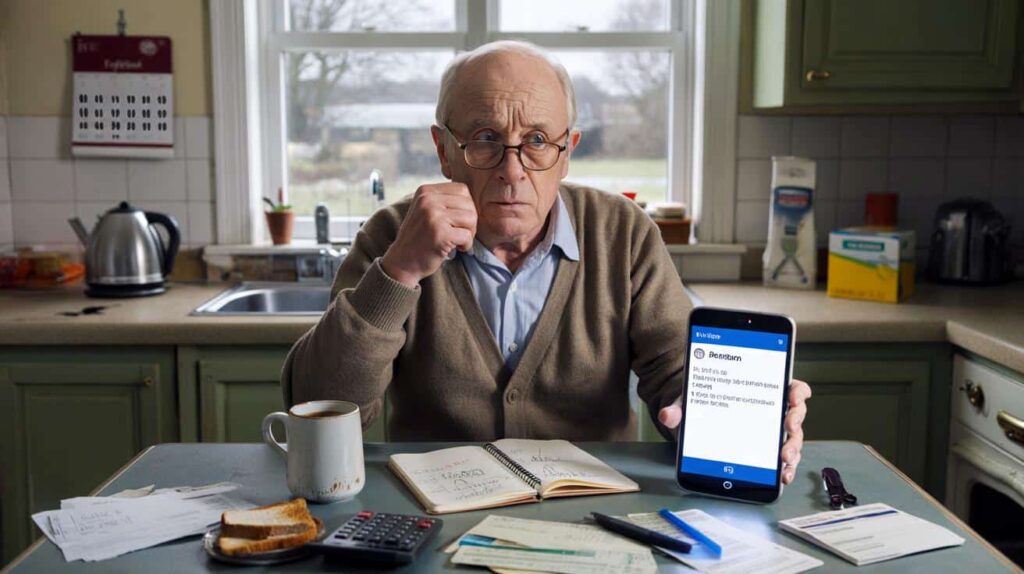

The email landed in Graham’s inbox on a grey Tuesday morning, just after he’d boiled the kettle. “Notification regarding your State Pension,” the subject line read. He clicked, half-distracted, already thinking about toast. Then the numbers flashed up on the screen: a confirmed reduction of about £140 a month, starting from February. The toast went cold.

He read the message three times, eyes snagging on phrases like “adjustment”, “recalculation” and “approved changes”. None of them sounded like what they really meant: less money, same bills.

Across the country, thousands of people had a similar moment that week. A quiet kitchen. A phone screen glowing. That sinking feeling.

Something big had just shifted in their supposedly “guaranteed” retirement.

What a £140 Monthly Cut Really Looks Like in Real Life

On paper, a £140 cut to the State Pension can look abstract. A neat line on a budget document or a tidy number in a minister’s quote. Once you put it into a real home, with real bills and real cupboards, it stops being a number and turns into a choice.

For many retirees, £140 isn’t “extra”. It’s the weekly food shop. It’s the winter heating top-up. It’s the bus pass, the birthday gifts for grandchildren, the just-about-manageable trip to see family.

When that amount disappears from February, it bites into something that already felt fragile. Nobody looks at their pension and thinks, “What can I do without?”

Marian, 69, from Manchester, did what a lot of people did: she grabbed a notebook and started scribbling. Her State Pension was already carefully stretched across rent, council tax, gas and electricity, a small phone bill, and a modest savings pot she was quietly proud of. Losing around £140 a month meant the savings line vanished in a single stroke.

She worked out that over a year, she’d be down nearly £1,700. That’s Christmas, gone. That’s the emergency dental work she’s been postponing, gone. That’s the new winter coat she’d been promising herself, postponed again.

“We’ve all been there, that moment when you stare at your bank statement and think, ‘What do I cut when there’s nothing left to cut?’” she said, folding the page over as if that could change the numbers.

Behind the scenes, the logic is brutally simple. Governments under pressure look for big budget lines where small percentage changes save billions. The State Pension is one of the biggest. Politicians speak of “sustainability”, “long-term balance” and “reforms”. For retirees, it lands as one thing: less cash, same life.

The £140 monthly reduction isn’t falling from the sky. It’s tied to recalculations, thresholds, and a reworking of commitments that were once presented as rock-solid. The famous triple lock has been questioned, recalibrated, tested.

Let’s be honest: nobody reading a manifesto in 2019 thought they’d be planning for a pension cut in 2026. Yet here we are.

How to React Practically When Your Pension Drops in February

The first useful move is painfully unglamorous: build a brutally honest one-page budget. No apps, no colour-coding, just a pen, paper, and your real numbers. Start with what will actually hit your account after the cut. Then list your essential outgoings: housing, utilities, food, transport, medication. Everything else comes second.

Once you have that, ring-fence a “non-negotiable core” – the bills that literally keep a roof, light and heat in your life. You might be surprised how clear it looks on a single page.

Only then look at the “flexible” zone: subscriptions, small luxuries, recurring direct debits you’ve stopped noticing. One by one, they become decisions, not habits. *That’s the uncomfortable part, but it’s where you regain some control.*

A lot of people react to news like this by freezing. The letter arrives, the numbers don’t add up, and the mind quietly shuts down. Days pass. The cut is “next month’s problem”. By the time February hits, the bank balance is already struggling. That silent delay is costly.

A more sustainable way is to treat the next few weeks as a preparation window, not a panic window. Talk out loud about it, even if it’s just with a friend over tea. Ask your energy provider about realistic payment plans. Check if you qualify for Pension Credit, Council Tax Reduction, Warm Home Discount or other lesser-known schemes that are rarely mentioned on TV.

There’s no shame in saying, “My numbers don’t work anymore.” The real damage comes from pretending they still do.

“People feel like they’ve broken some invisible rule if they can’t survive on their pension,” says Rebecca Hall, a community adviser in Birmingham. “But the system has shifted under their feet. They didn’t mismanage their lives. The rules of the game changed halfway through.”

- Call a free advice service – Citizens Advice, Age UK and local welfare rights teams can check benefits you might be missing.

- Ask your council about discretionary support funds – these are often under-publicised and time-limited.

- Review old debts – sometimes a small negotiated reduction or longer plan creates monthly breathing room.

- Look for community assets – warm hubs, community kitchens, repair cafes and free social clubs reduce hidden daily costs.

- Keep a “money diary” for 30 days – not forever, just long enough to spot leaks that quietly drain £20–£30 a week.

What This Pension Cut Says About How We Treat Retirement

When a country decides that cutting retired people’s income by £140 a month is acceptable policy, it says something about its priorities. The State Pension was sold for decades as a foundation, a promise: pay in all your working life, and you won’t be left behind. That promise now feels conditional, written in pencil.

For younger workers watching parents and grandparents panic, it chips away at trust. If the basic floor of old-age income can be lowered with a few votes and a press release, what else can move? What does “planning for retirement” even mean when the reference point keeps shifting?

Some will quietly adapt. Some will go back to part-time work in their late 60s or early 70s. Others simply can’t work, can’t move, can’t downsize. The cut lands hardest on those with the least room to manoeuvre, as cuts always do.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Scale of the cut | Around £140 less per month from February, close to £1,700 a year | Helps you translate a policy line into the real impact on your household budget |

| First response | One-page budget, prioritising core bills and reviewing “flexible” spending | Gives you a concrete starting action instead of staying stuck in worry |

| Support options | Advice charities, local council schemes, benefit checks, debt advice | Opens doors to help that many people don’t realise they can ask for |

FAQ:

- Will every pensioner lose exactly £140 a month?Not necessarily. The figure of around £140 is an average benchmark tied to the approved changes, but the exact amount you lose depends on your personal entitlement, previous contributions, and any additional top-ups or benefits you receive.

- When will I see the cut in my bank account?The reduction is scheduled to apply from pension payments dated in February. That means the first lighter payment will typically appear on your usual February payday, so your January payment should remain at the current level.

- Can I appeal or challenge the cut?You can challenge calculation errors, but not the rule change itself. If you suspect your new payment has been miscalculated, contact the pensions helpline, ask for a written breakdown, and seek independent advice before you accept the figure as final.

- Is there any way to “replace” the lost £140?