What started as a playful thought experiment about moving a sofa through a corner became one of geometry’s most stubborn open problems — and a 31‑year‑old Korean researcher has now brought it to a close with a 119‑page proof, written almost entirely by hand.

The sofa question that refused to go away

Back in 1966, austro‑Canadian mathematician Leo Moser posed a problem that sounded almost like a party trick. Picture a corridor shaped like an “L”, each arm exactly one metre wide. What is the largest possible rigid, flat shape — think of a solid sofa seen from above — that can be pushed around the corner without lifting or bending it?

This became known as the “moving sofa problem”. The rules were clear. The corridor width was fixed. The shape had to stay entirely inside the corridor. It could slide and rotate, but not flex. The goal was to maximise the area of the shape.

6 minutes of darkness get ready for the longest eclipse of the century that will turn day into night

6 minutes of darkness get ready for the longest eclipse of the century that will turn day into night

The question is simple enough to explain to a teenager, yet hard enough to resist the best mathematicians for nearly 60 years.

By the late 1960s, researchers began proposing candidate shapes. In 1968, British mathematician John Hammersley designed a clever sofa‑like figure with an area of about 2.2074 square metres. It fit the corridor and became the benchmark.

Then, in 1992, American mathematician Joseph Gerver pushed things further. He produced a wildly intricate shape, pieced together from many smooth curves. Its area: roughly 2.2195 square metres. For years, Gerver’s shape was thought to be the champion — but no one could prove that nothing larger could work.

Computers were thrown at the problem. Simulations tested variations, refined curves and tried to squeeze out extra fractions of area. Yet the uncertainty remained. Was Gerver’s shape truly optimal, or just a very good guess?

How a conscript stumbled on a legendary puzzle

The story took a new turn far from North America or Europe. During his mandatory military service in South Korea, Baek Jin‑eon was assigned to the National Institute for Mathematical Sciences, a rare posting that allowed him to keep doing research.

There he first read about the moving sofa problem. What grabbed him was not only the difficulty, but the strange lack of a solid theoretical framework around it. For a problem this famous, the foundations still felt ad hoc — a collection of constructions and numerical experiments, rather than a unified theory.

Baek decided to build the missing framework first, then attack the problem from the ground up, without leaning on computer searches.

He carried that obsession into his PhD at the University of Michigan, and later to the June E. Huh Center for Mathematical Challenges at the Korea Institute for Advanced Study. For seven years, the moving sofa problem sat at the centre of his life.

Colleagues describe a process that was both slow and relentless: sketching ideas, formalising them, finding contradictions, starting again. Baek himself has compared the cycle to alternating dreams and awakenings — flashes of hope followed by the harsh clarity of a new error found on page 75.

A 119‑page proof, almost no computers

Late in 2024, Baek posted a 119‑page manuscript on the scientific preprint server arXiv. The paper claims a definitive result: Gerver’s 1992 sofa is not just good — it is mathematically optimal.

No rigid, flat shape with area larger than Gerver’s can be pushed around the one‑metre L‑shaped corner without colliding with the walls.

That statement sounds straightforward. The machinery behind it is anything but. Baek’s key move was to turn an informal puzzle into a precise optimisation problem. He rephrased the entire question in terms of the possible positions and orientations of the sofa as it moves.

Instead of asking “what shape works best?”, he studied the space of all allowed motions through the corridor and the constraints that motion imposes on the boundary of the shape. From there, he derived rigid conditions that any optimal sofa must satisfy — and showed that these conditions uniquely lead to Gerver’s configuration.

Strikingly, Baek avoided heavy numerical computation. There were no large‑scale simulations, no automated search over millions of shapes. The proof rests on classic tools: careful geometry, inequality chains and meticulous case analysis.

What mathematicians checked for years with computers

For non‑specialists, it helps to see what previous work tried to do. Roughly speaking, researchers used software to:

- Approximate the best possible shape by tweaking curves and corners.

- Simulate how these shapes move through the corridor and track collisions.

- Estimate upper bounds on area by ruling out families of shapes.

Baek’s contribution is that he no longer needs to “estimate” in this way. The argument draws a line and says: beyond Gerver’s area, any hypothetical sofa would violate at least one geometric constraint, so such a shape simply cannot exist.

A reminder that pencil‑and‑paper maths still bites

The timing of this breakthrough matters. Mathematics has become deeply entangled with computation, from machine‑checked proofs to AI‑assisted conjectures. In that context, a major geometric problem solved with almost no code sends a strong signal.

The result showcases human‑style reasoning at full stretch, at a moment when many expect algorithms to lead the way.

Baek, now 31, continues to work in combinatorial geometry and optimisation within a rapidly growing Korean research ecosystem. His paper is under review at the prestigious Annals of Mathematics, a journal known for its stringent standards. If accepted, it will cement the moving sofa problem as closed and elevate Baek into a small group of researchers who have resolved long‑standing “folklore” questions.

Beyond prestige, the story taps into a more cultural shift. South Korea has invested heavily in basic science over the past two decades, trying to complement its industrial strength in electronics and engineering. High‑profile results like this indicate that the country’s maths community is starting to deliver on that long‑term bet.

Why anyone should care about a hypothetical sofa

From the outside, optimising the shape of a fictional sofa sounds niche. Yet the underlying maths fits into a broader family of questions with real‑world echoes.

Problems about squeezing objects through constrained spaces appear in robotics (navigating a robot arm around obstacles), logistics (planning how to move large components through factories), and even computer graphics (path planning in virtual environments). All these areas rely on understanding “configuration spaces” — sets of all possible positions an object can take without hitting anything.

| Concept | Simple description | Where it shows up |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration space | All allowed positions and angles of an object | Robot navigation, animation, motion planning |

| Geometric optimisation | Finding the “best” shape under strict rules | Design, packing problems, engineering |

| Rigidity constraints | Object can move but not stretch or bend | Manufacturing, architecture, materials science |

The moving sofa problem serves as a clean testbed: the corridor is simple, the rules are sharp and the target — maximal area — is easy to state. That clarity lets mathematicians stress‑test techniques that can later be adapted to more practical scenarios, where the environment is messy and the objects are not perfect mathematical sets.

Key notions behind the puzzle

What “optimal” means here

When mathematicians say Gerver’s sofa is optimal, they mean something very precise: among all possible flat, rigid shapes that can be moved around the corner, none has strictly larger area. Many shapes can make the turn; some are even easier to handle. But if you want the absolute largest surface, you cannot beat Gerver’s design.

That notion of optimality matters beyond sofas. In engineering, “good enough” designs might be acceptable. In pure maths, the target is sharper: prove that no better solution exists anywhere, not just within a limited search.

Thought experiments that train intuition

The moving sofa has also lived a parallel life as a classroom toy. Lecturers use it to show students that a question can be:

- Easy to understand.

- Hard to formalise rigorously.

- Extremely challenging to close definitively.

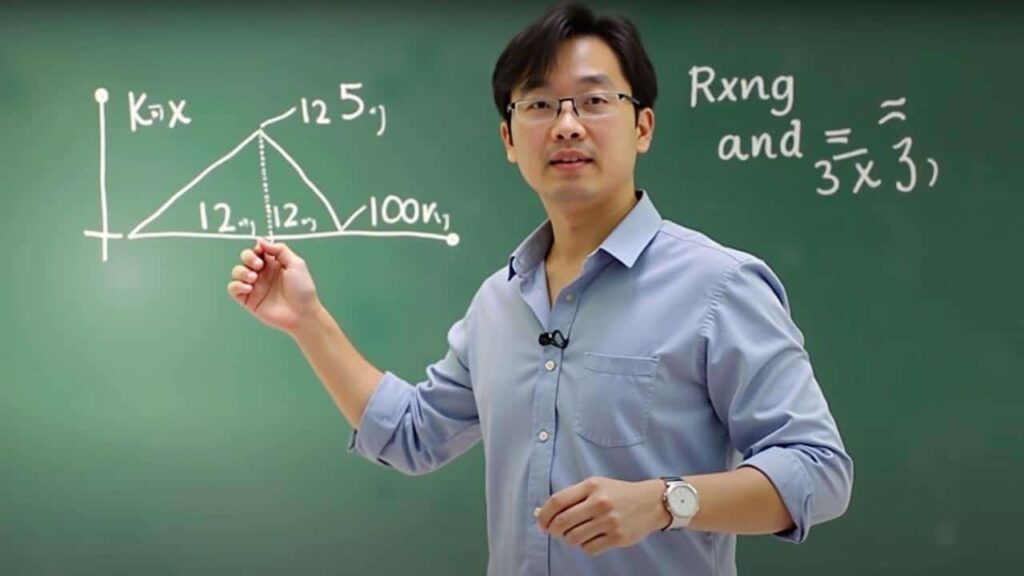

One common exercise is to let students sketch their own “best sofas”, then simulate them using basic software or paper cut‑outs in a cardboard corridor. The moment their carefully drawn shape gets stuck on the inside corner drives home how constraints bite in geometry.

Beyond the sofa: what comes next

With this problem apparently settled, attention will likely shift to variants. What if the corridor width changes along its length? What if the object can flex within limits? What if the corridor turns twice instead of once, or branches like a maze?

Each twist adds new degrees of freedom and fresh difficulties. Yet the methods Baek developed — formalising movement, pinning down necessary conditions, ruling out whole families of shapes — may transfer. Young researchers now have a new toolkit and a benchmark for the kind of persistence such puzzles demand.

For readers curious about trying something similar at home, a simple activity works well: draw an L‑shaped corridor on graph paper, cut out different cardboard shapes, and test which ones can “walk” around the bend without lifting the piece. That small game mirrors, in very rough form, the same constraints that occupied professional mathematicians across three generations.

The moving sofa problem is now, most likely, closed. The corridor stays the same width, the corner still turns at ninety degrees, but thanks to a patient Korean mathematician, the shape that squeezes through with maximal area no longer hides in the shadows of conjecture.