It’s just after 7:42 in the morning. The kettle has already clicked off, but you’re still standing there, hand resting on the counter, not quite ready to pour. Your eyes drift to the window, then to the clock, then back again. Nothing is wrong. And yet something feels slightly out of step.

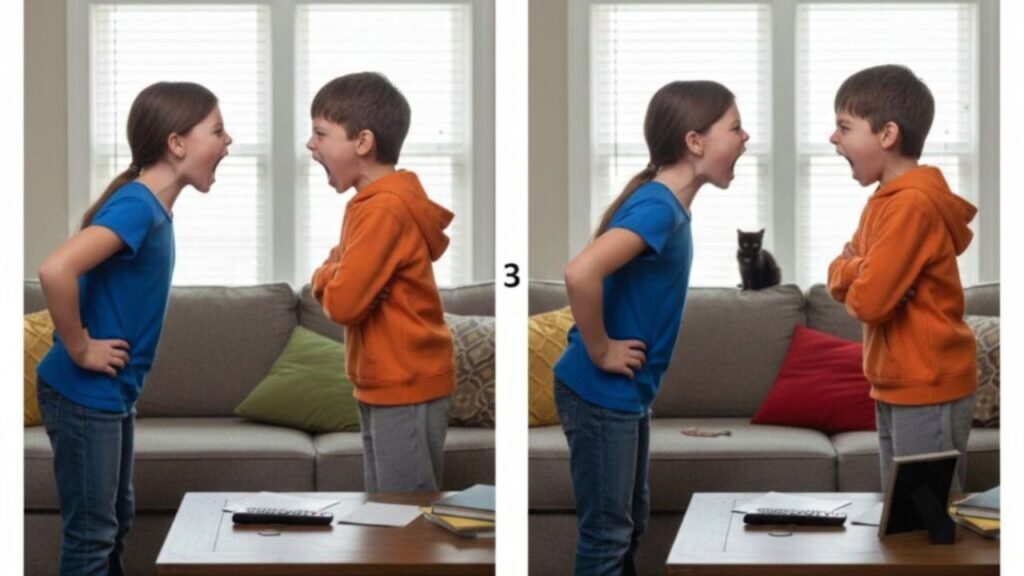

You might later sit with your phone or a newspaper and notice one of those small visual puzzles — two nearly identical pictures, a girl and a boy frozen mid-shout, and the simple instruction to spot three differences in nine seconds. You start looking. You know how this works. And still, it takes longer than you expect.

That moment — the pause, the quiet irritation, the soft surprise — lingers longer than the puzzle itself.

The subtle feeling of being out of sync

Many people in their fifties, sixties, and beyond describe a similar sensation. Not confusion. Not decline. Just a sense that the world is moving on a slightly different rhythm now.

You notice it when conversations overlap and you miss the exact moment to speak. Or when you re-read the same paragraph twice, not because you don’t understand it, but because it didn’t quite land the first time. Or when a game meant to be “quick and easy” suddenly asks more of your attention than you were prepared to give.

It’s not that your mind is failing you. It’s that the tempo has shifted.

Why a simple visual challenge can feel harder than it used to

On the surface, a 9-second visual challenge looks trivial. Two images. Three differences. A countdown ticking somewhere in the background.

But beneath that simplicity is something more revealing. These challenges rely on rapid visual scanning, quick comparison, and a kind of mental urgency that assumes your attention is ready to sprint on command.

Earlier in life, that sprint felt natural. Your attention could leap from detail to detail without much effort. Now, attention behaves a little differently. It prefers to arrive, settle, and then explore.

This isn’t a flaw. It’s a change in rhythm.

A quiet shift in how the brain pays attention

As we age, the brain becomes more selective. It doesn’t scatter itself as easily. Instead of grabbing everything at once, it leans toward depth over speed.

That means you may notice big patterns more quickly, but small visual discrepancies — a slightly different eyebrow, a missing button, a shadow that falls the wrong way — take longer to register.

The clock ticking in a “9-second challenge” doesn’t help. Time pressure narrows attention. And when attention narrows, subtle details slip past.

So when you don’t immediately spot the third difference, what you’re experiencing isn’t slowness. It’s caution.

A real-life moment many recognise

Marianne, 62, laughs about this now. She was sitting with her grandson, looking at one of these puzzles on a tablet. He spotted all three differences almost instantly.

“I kept seeing the shouting first,” she said. “The expressions. The feeling of the picture. I had to remind myself to look past that.”

It wasn’t that Marianne couldn’t see. It was that her attention went first to meaning, not measurement.

What’s actually happening in your mind

Visual challenges like this ask the brain to do three things at once: observe, compare, and decide — quickly.

Over time, the brain becomes less interested in rushing to decide. It prefers to observe a little longer. It weighs context. It notices emotion before detail.

The girl and boy shouting aren’t just shapes and colours. They’re faces. Expressions. Stories. Your mind registers those before it counts missing elements.

This is why you may feel momentarily “behind” — not because you are, but because your mind is doing more than the task requires.

Gentle ways people naturally adjust

Without realising it, many people already adapt to this shift. They give themselves a little more time. They ignore the countdown. They focus on one area of the image instead of scanning everything at once.

These aren’t strategies to improve performance. They’re ways of respecting how attention works now.

- Letting your eyes rest before actively searching

- Looking at one section of an image at a time

- Ignoring artificial time limits when possible

- Allowing the emotional impression to pass before focusing on details

- Accepting that “later noticing” is still noticing

What these puzzles quietly reveal about ageing

A visual challenge is never just a game. It reflects assumptions about speed, urgency, and efficiency.

But later in life, awareness becomes broader, not narrower. You may take longer to spot the missing button, but you notice the tension in the scene immediately. You sense the mood. You understand what’s happening between the figures.

That kind of perception isn’t measured in seconds.

“I don’t miss things more than I used to. I just see more before I decide what matters.”

Reframing the moment

When you don’t “win” a 9-second visual challenge, it can stir an unexpected feeling — a flicker of self-doubt, or the sense that something has slipped away.

But what’s actually happening is quieter than that.

Your attention has matured. It doesn’t rush toward differences. It absorbs the whole picture first.

And in a world that constantly asks you to be faster, sharper, and more immediate, that slower noticing is not a loss. It’s a different way of being present.

You’re not out of sync with yourself. You’re simply no longer tuned to artificial urgency.

What stays with you after the puzzle

Long after the image disappears, the feeling remains. Not frustration, but recognition.

You realise that many things now ask you to perform on a timeline that doesn’t match how you experience life. And that’s okay.

Some differences are meant to be spotted quickly. Others are meant to be understood slowly.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Attention changes with age | The mind favours depth over speed | Reduces unnecessary self-doubt |

| Time pressure affects perception | Countdowns narrow focus | Encourages gentler self-expectations |

| Slower noticing has strengths | Emotion and context are seen first | Affirms the value of lived experience |