Instead of blasting the whole body with toxic drugs or high-energy beams, scientists are testing a targeted “heat attack” that aims to wipe out cancer cells while leaving nearby healthy tissue almost untouched.

A gentler way to fight cancer

For decades, cancer treatment has relied on powerful weapons. Chemotherapy poisons fast-growing cells. Radiotherapy bombards tumours with radiation. Surgery removes entire chunks of tissue to be safe.

These tools save lives, but the price can be brutal: nausea, hair loss, fatigue, burns, nerve damage, scars, long-term pain. Patients often say they feel as if the cure is hurting them nearly as much as the disease.

A research partnership between the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Porto is now testing a different strategy. Instead of treating the whole body, their approach aims to seek out cancer cells, heat them from the inside, and spare as many healthy cells as possible.

This light-based therapy destroyed up to 92% of skin cancer cells in lab tests while leaving nearby healthy cells largely unharmed.

The study, published in the journal ACS Nano, uses tiny particles of tin oxide and a near‑infrared LED light. Together, they act like a remote-controlled heater that only turns on where cancer is present.

How a simple LED becomes a cancer weapon

The technology is built around two main components: a near-infrared light source and engineered nanoparticles.

Meet the tin “nanoflakes”

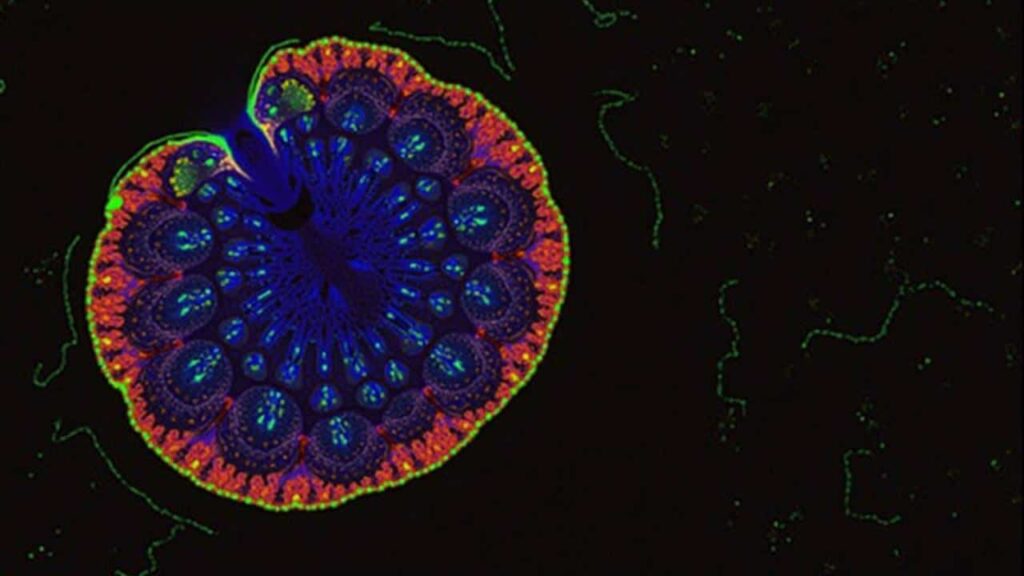

The particles, called SnOx nanoflakes, are made from tin oxide and measure just a few billionths of a metre across. At that scale, materials can behave in unusual ways. In this case, the flakes absorb near‑infrared light and rapidly convert it into heat.

When these nanoflakes are placed near cancer cells and exposed to a specific wavelength from an LED, they warm up enough to damage and kill the malignant cells.

The key is localisation: the heat is generated exactly where the particles sit, instead of frying everything in the path of a beam.

In lab experiments on skin cancer cells, around 30 minutes of LED exposure destroyed roughly 92% of the malignant cells. Tests on colorectal cancer cells showed about 50% elimination, suggesting that different cancers may respond differently, but that the principle works across several types.

Why LEDs change the game

Photothermal cancer treatments are not new. Lasers have been used for years to heat metallic nanoparticles inside tumours. Yet lasers tend to be expensive, bulky, and sometimes aggressive for nearby tissue.

This new approach replaces high‑power lasers with relatively low‑cost near‑infrared LEDs. These lights are widely used in consumer products, such as remote controls and cosmetic devices, and they are easier to integrate into small, portable equipment.

- LEDs: cheaper, compact, can be used in simple devices

- Near‑infrared light: penetrates tissue better than visible light

- Tin nanoflakes: act as tiny heaters that activate only under the right light

- Targeted heating: reduces damage to healthy cells

Researchers also tested the thermal stability of the particles over repeated heating cycles. The nanoflakes continued to perform reliably, which is crucial if patients need several treatment sessions over weeks or months.

From hospital ward to home care?

One of the most striking possibilities raised by the team is where this therapy could be delivered.

Traditional chemotherapy often requires long, supervised infusions. Radiotherapy needs heavy, shielded rooms. In contrast, a treatment based on a small LED lamp and injectable nanoparticles could, in theory, be adapted for much more flexible use.

Scientists are already talking about portable devices that patients might wear or apply to the skin after surgery, targeting leftover cancer cells before they regroup.

For superficial tumours, such as many skin cancers, a patient might one day go home with a compact patch or handheld applicator. The device would shine near‑infrared light onto the area where nanoparticles have been delivered, treating small recurrences without hospital admission.

This idea remains speculative for now. Clinical trials have not started, and any at‑home use would face strict safety and regulatory hurdles. Still, the concept fits a broader shift in oncology: more targeted, more personalised, and, when possible, less tied to hospital beds.

Which cancers could benefit first?

The researchers are particularly focused on cancers that sit close to the surface of the body or are reachable with minimal surgery.

| Potential target | Why it makes sense |

|---|---|

| Skin cancers | Easy light access, can treat surgical margins or small lesions |

| Breast cancer (localised) | Could target tumour beds after surgery to reduce recurrence |

| Colorectal tumours | Endoscopic tools could deliver light to internal lesions |

The UT Austin Portugal programme is already funding work to adapt the approach to breast cancer. In that scenario, surgeons might remove the main tumour, then use nanoparticles and LED light to clean up microscopic cells left behind in the surrounding tissue.

Benefits and unanswered questions

The potential benefits are clear: fewer side‑effects, less damage to healthy tissue, and possibly shorter recovery times. A localised treatment could also be combined with systemic therapies such as immunotherapy or targeted pills, attacking the tumour from several angles at once.

At the same time, big questions remain. Scientists need to understand how long nanoparticles stay in the body, how they are cleared, and whether they accumulate in organs over time. Regulators will want strong evidence that the particles do not trigger unexpected inflammation or long‑term toxicity.

How photothermal therapy actually kills cancer cells

For non‑specialists, the idea of “cooking” cancer cells can sound either scary or vague. The process is more controlled than it might appear.

Cells can only tolerate a narrow temperature range. When local temperature rises above roughly 42–45°C for long enough, proteins start to unfold and vital structures break down. Cancer cells, already stressed and dividing rapidly, can be particularly sensitive to this heat.

The goal is not to boil tissue, but to nudge the temperature just high enough that malignant cells cannot survive, while nearby healthy cells recover.

Because the tin nanoflakes sit right next to or inside the cancer cells, the heat remains highly local. By adjusting the intensity and duration of LED exposure, doctors could fine‑tune how much damage is done and where.

What this might look like for a patient

Imagine a person diagnosed with a small, early‑stage skin cancer. Today, they might undergo surgery, sometimes followed by radiotherapy if surgeons worry that stray cells remain.

With this new approach, the sequence might change. Surgeons could still remove the visible tumour, then inject or apply SnOx nanoparticles around the wound edges. A nurse would place an LED device over the site for a set time, heating any leftover cancer cells. The patient would feel warmth, but not the burning or systemic side‑effects associated with radiation or chemotherapy.

If the technology advances further, patients with recurring superficial lesions could receive several sessions across a few weeks, each one lasting under an hour. The therapy might become one tool among many, chosen for suitable cases rather than replacing all existing treatments.

Key concepts patients might hear about

As this type of therapy progresses, a few technical terms are likely to appear in clinic conversations:

- Photothermal therapy: treatment that uses light to generate heat inside tissue and kill targeted cells.

- Near‑infrared (NIR): light just beyond visible red, able to pass deeper into skin than standard light.

- Nanoparticles: ultra‑small particles engineered for medical tasks, such as drug delivery or local heating.

- Targeted therapy: an approach designed to act on specific cells or molecules, rather than the entire body.

If this tin‑based LED technique reaches clinics, oncologists will need to explain not only what it can do, but also where its limits lie. Patients will likely receive it alongside existing treatments, not as a standalone “magic bullet”.

For now, the work in Texas and Porto stays inside the lab. Yet the idea that an inexpensive LED device and engineered particles could quietly kill cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue is already reshaping how researchers think about the next generation of cancer care.