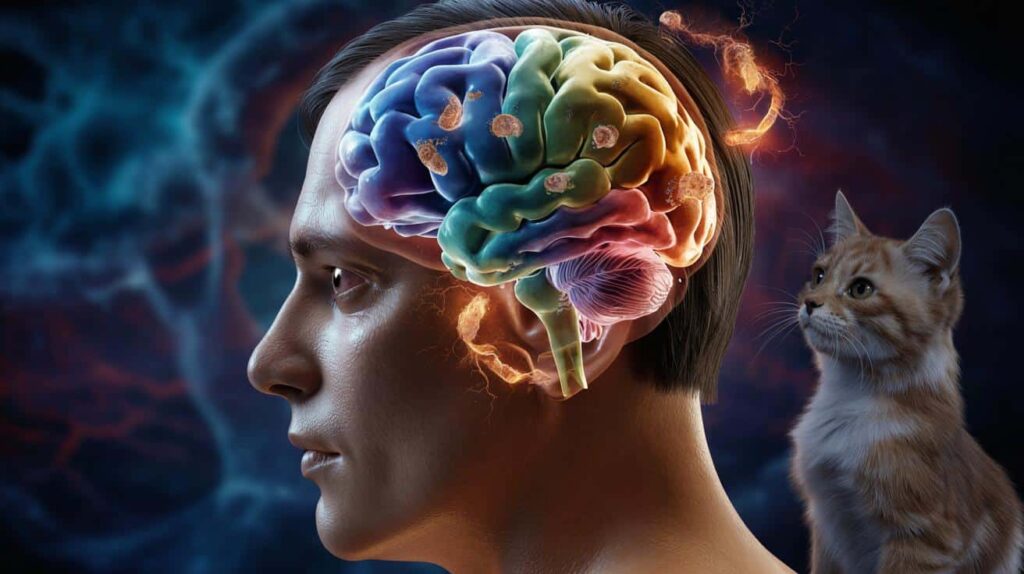

Scientists now argue that a microbe infecting billions worldwide keeps nudging the brain, potentially shaping behaviour, emotions, and long‑term health in ways we are only beginning to grasp.

What parasite are we talking about?

The parasite in question is Toxoplasma gondii, often shortened to toxoplasma. It is a microscopic organism that can infect almost all warm‑blooded animals, but it reproduces sexually only in cats. That connection to felines has earned it the nickname “the cat parasite”.

People pick it up mainly by handling cat litter, eating undercooked meat, or consuming food and water contaminated with parasite eggs. Once inside the body, it can travel to the brain, where it forms tiny cysts.

Boiling lemon peel, cinnamon and ginger : why people recommend it and what it’s really for

Boiling lemon peel, cinnamon and ginger : why people recommend it and what it’s really for

Toxoplasma infection is so common that up to a third of the global population may carry it, often without knowing.

For years, the medical consensus was clear: after an initial brief infection, toxoplasma hides inside cells, forms tissue cysts and then lies dormant, causing little or no trouble in healthy people. Recent studies are now challenging that assumption.

The ‘dormant’ myth under pressure

New lab work and brain imaging suggest that toxoplasma cysts are not simply sitting there quietly. Instead, they may keep interacting with nearby brain cells and the immune system throughout life.

Researchers have observed that the parasite can:

- Alter the activity of neurons near infected areas

- Trigger low‑level inflammation that persists for years

- Interfere with key brain chemicals such as dopamine and GABA

- Change how immune cells behave in brain tissue

None of this automatically means dramatic symptoms. Many people with toxoplasma never feel anything obvious. But the idea that the parasite is biologically inactive no longer fits the data.

The new picture is of a long‑term intruder that keeps whispering to the brain, not a guest asleep in the attic.

How toxoplasma reaches and settles in the brain

After you ingest toxoplasma, it first multiplies in the gut and nearby lymph nodes. The immune system quickly responds, and the parasite changes strategy. Instead of racing through the blood as fast‑growing forms, it transforms into slower cyst‑forming stages.

These stages can cross into organs, including the brain and the eye. Inside the brain, they wrap themselves in protective cyst walls and set up permanent residence in areas involved in emotion, decision‑making and movement.

| Stage | Where it lives | Main feature |

|---|---|---|

| Acute (tachyzoite) | Blood and many organs | Rapid multiplication, flu‑like symptoms |

| Chronic (tissue cyst) | Brain, muscles, eye | Long‑term presence, subtle effects |

This chronic stage is what was long labelled “latent” or “dormant”. What researchers now see is ongoing dialogue between these cysts, neurons and immune cells.

Links to behaviour and mental health

Several population studies have tied toxoplasma infection to changes in behaviour and a higher risk of certain psychiatric conditions. These findings are still debated, and they do not prove that the parasite causes mental illness by itself.

Yet the pattern is intriguing. Some research has found a stronger presence of toxoplasma antibodies in people with:

- Schizophrenia

- Bipolar disorder

- Depression

- Suicidal behaviour

Animal experiments add another layer. Infected rodents lose their instinctive fear of cat odour and become more willing to explore risky environments. That suits the parasite nicely, since it needs cats to complete its life cycle.

When a parasite tweaks behaviour in a way that helps it reach its next host, scientists pay close attention.

In humans, the effects seem subtler: shifts in risk‑taking, slower reaction times, or slight changes in personality traits such as impulsivity or sociability. These are not dramatic enough to diagnose from the outside, but at the population level, they show up as measurable trends.

Who faces the greatest risk?

Most healthy adults control toxoplasma fairly well. The biggest dangers arise for people with weakened immune systems and for unborn babies.

Pregnancy and congenital infection

If a woman catches toxoplasma for the first time during pregnancy, the parasite can cross the placenta. That can lead to miscarriage or long‑term problems for the baby, including seizures, visual impairment and learning difficulties. This is why many prenatal guidelines advise pregnant people to avoid cleaning cat litter and to handle raw meat with care.

Immunocompromised patients

In people undergoing chemotherapy, living with HIV without treatment, or taking strong immunosuppressive drugs after organ transplant, a seemingly “quiet” infection can reactivate. That can cause brain inflammation known as toxoplasmic encephalitis, with headaches, confusion, seizures and, without prompt treatment, death.

These severe cases show that the parasite never really leaves. It stays, contained but active, waiting for a drop in defences.

How scientists think the parasite shapes the brain

Several mechanisms are under study to explain how toxoplasma might influence brain function.

- Neurotransmitter changes: The parasite carries genes that interact with dopamine pathways. Dopamine is a key chemical for motivation, reward and movement.

- Chronic inflammation: Long‑term immune activation can slowly alter connections between neurons and affect mood and cognition.

- Direct cell manipulation: Toxoplasma injects proteins into host cells that can switch genes on or off and reshape cell behaviour.

- Circuit rewiring: Infected brain regions may remodel themselves over time, subtly changing how signals travel through networks.

New data paints toxoplasma less as a passive passenger and more as a careful editor of neural circuits.

Can the infection be treated or prevented?

Current drugs kill the fast‑growing forms of toxoplasma but struggle against the tough cysts in the brain. Treatment for chronic infection is usually reserved for high‑risk patients, such as those with HIV or transplant recipients, or for severe eye disease.

For everyone else, prevention still does the heavy lifting. Common advice includes:

- Cooking meat thoroughly, especially pork, lamb and game

- Washing fruits and vegetables before eating

- Wearing gloves when gardening or handling soil

- Cleaning cat litter daily and washing hands afterwards

- Keeping cats indoors so they hunt less and pick up fewer parasites

Several labs are working on vaccines for animals, especially cats and livestock, to cut transmission to humans. A widely available human vaccine remains a long‑term goal.

What this means for everyday health

For most people, toxoplasma is one more factor among many that can nudge mental and physical health over decades. Genetics, upbringing, stress, infections, sleep, diet and social conditions all interact.

A person carrying toxoplasma will not automatically develop depression or schizophrenia. The parasite might add a small extra weight to an already complex balance, tipping some individuals at vulnerable moments.

Researchers are now using brain scans, blood markers and long‑term follow‑up studies to see how these subtle influences play out. Future work may reveal that treating certain infections early, or calming brain inflammation, reduces the risk of later psychiatric problems.

Key terms that help make sense of the story

Several technical expressions often appear in discussions about toxoplasma and the brain:

- Latent infection: A long‑lasting infection that produces few or no clear symptoms but still involves living microbes.

- Neuroinflammation: A sustained immune response inside the brain, which can affect memory, mood and thinking.

- Seroprevalence: The proportion of a population that shows antibodies to a microbe, signalling past or current infection.

Understanding these concepts helps frame toxoplasma not as a horror‑movie monster, but as a widespread, quietly active parasite that probably interacts with brain health in small but meaningful ways throughout life.