For decades, a common brain parasite was treated as biological background noise, quietly ignored after the first infection.

New research suggests that assumption may be badly wrong, raising fresh questions about how a tiny organism could shape human health, behaviour and even public policy.

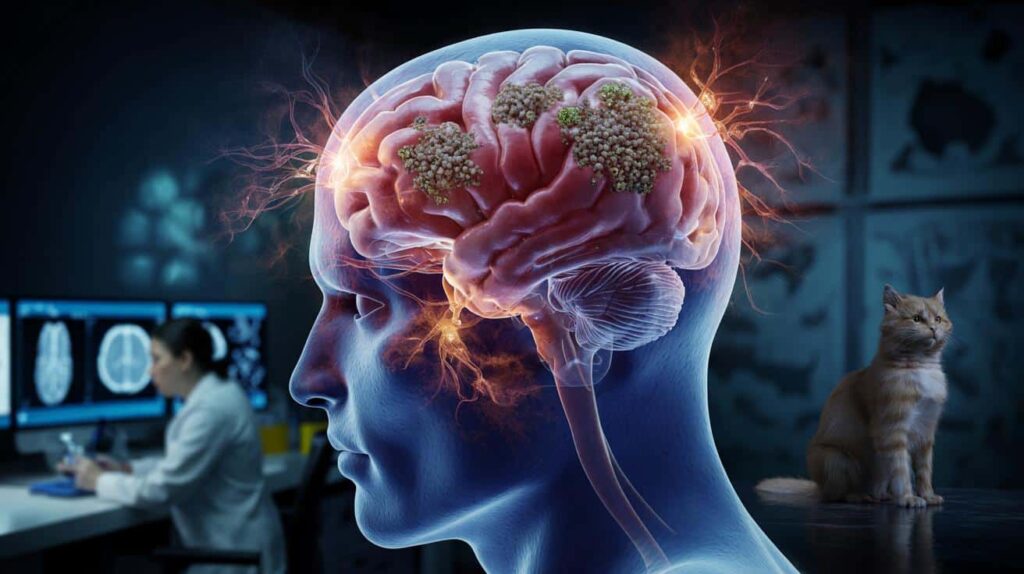

A quiet parasite hiding in plain sight

The parasite in question is Toxoplasma gondii, often simply called toxoplasma. It infects an estimated one in three people globally. Many never know they have it.

People usually catch toxoplasma by eating undercooked meat, handling contaminated soil, or coming into contact with cat faeces. Cats are the parasite’s “definitive host”, where it reproduces sexually.

After an initial short phase of active infection, the parasite forms microscopic cysts in muscles, eyes and the brain. For years, the standard view was simple: once the infection became chronic, it went quiet and stayed that way.

New studies challenge the idea that toxoplasma becomes biologically silent in the brain, suggesting ongoing activity long after infection.

This shift matters because a supposedly “dormant” infection attracts less attention from doctors, health agencies and even funding bodies. If chronic toxoplasma is more active than believed, that complacency could carry a cost.

From dormant passenger to active player

The new work, led by teams in neurobiology and infectious diseases, used advanced imaging, molecular tracking and animal models. Researchers followed what happens to brain cells long after the first infection is “over”.

Instead of finding harmless cysts sitting quietly, they saw signs of low-level inflammation, altered signalling between neurons and subtle immune responses that persisted for months.

The parasite appears to keep sending signals and interacting with brain tissue, rather than simply parking itself and shutting down.

Lab experiments showed that cysts can occasionally reactivate, release parasite molecules and even affect how brain cells communicate. The process is not dramatic enough to cause acute illness in most healthy people, but it may slowly nudge brain circuits and immune systems over time.

What does toxoplasma actually do in the brain?

Scientists have long known that toxoplasma can cause severe disease in people with weakened immune systems and in babies infected before birth. The fresh concern lies in the vast number of healthy adults who carry the parasite without symptoms.

Several recent studies, while not definitive, link chronic toxoplasma infection with:

- Higher risk of some psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

- Subtle changes in reaction time and risk-taking behaviour

- Increased chance of traffic accidents in some populations

- Possible contribution to long-term inflammation linked to cardiovascular disease

In animals, the effects are more striking. Infected rodents famously lose their instinctive fear of cat odour, making them easier prey and helping the parasite complete its life cycle in the cat’s gut.

In humans, any impact seems far weaker and highly variable. Still, the idea that a common infection might gently tug at our moods, decisions or vulnerability to psychiatric illness has attracted growing attention.

Evidence from population studies

Large-scale epidemiological studies provide some of the strongest, if still debated, signals. Researchers have compared blood samples from thousands of people, looking at who carries antibodies to toxoplasma and what health conditions they have.

These studies do not prove cause and effect, but several patterns keep appearing. People with toxoplasma antibodies, on average, show slightly higher rates of certain mental health diagnoses and self-harm, even after adjusting for social and economic factors.

Scientists are cautious, but the repeated associations push against the comforting idea that chronic toxoplasma is completely harmless.

Why scientists once thought it was harmless

The earlier view of toxoplasma as a benign “stowaway” had some logic. Most infected people never fall seriously ill. The immune system usually brings the acute infection under control. Classic medical teaching described the next stage as lifelong latency.

Diagnostic tools also shaped expectations. Standard blood tests identify antibodies that show past exposure, not current activity. Brain scans to detect individual cysts are rarely performed outside severe cases. Without clear signs of damage, the default assumption became: no symptoms, no problem.

The new generation of imaging and molecular techniques tells a more nuanced story. Instead of cleanly separated “acute” and “chronic” phases, scientists see something more like a simmering state — not fully active, not fully silent.

Who faces the greatest risk?

Most people with a healthy immune system will never notice any direct effect from toxoplasma. Even if the parasite does tweak brain function, the influence appears modest at an individual level.

Risk rises sharply in certain groups:

| Group | Main concern |

|---|---|

| Pregnant women (new infection) | Transmission to the fetus, causing miscarriage, eye and brain damage or developmental delay |

| People with weakened immunity | Reactivation of cysts in the brain, leading to toxoplasmic encephalitis, seizures and confusion |

| Organ transplant recipients | Parasite activation when immune suppression drugs are started |

For these groups, toxoplasma has never been considered benign, which is why screening and targeted treatment already exist in many healthcare systems.

Public health questions on the horizon

The suggestion that chronic toxoplasma may have subtle but widespread effects raises awkward questions. If up to a third of humanity carries a biologically active brain parasite, should public health measures change?

Experts currently point to four priority areas:

- Improving food safety, especially thorough cooking of meat

- Clearer guidance for cat owners, particularly during pregnancy

- Better surveillance of psychiatric and neurological links in large cohorts

- Development of drugs that target cyst stages without serious side effects

Even small individual effects could become significant when multiplied across millions of people carrying the same infection.

There is also a social dimension. Toxoplasma is more common where food hygiene is weaker and veterinary control is patchy, meaning any risk is not evenly shared across populations.

What cat owners and families can actually do

News about a brain parasite easily triggers anxiety, especially among people who live with cats. Health agencies stress that cat ownership and safety can coexist, with a few practical steps:

- Wash hands thoroughly after cleaning litter trays or gardening

- Change cat litter daily so parasite eggs do not have time to become infectious

- Avoid feeding cats raw or undercooked meat

- Keep cats indoors where possible to reduce hunting and infection cycles

- Pregnant people should delegate litter cleaning, or use gloves and a mask

These measures do not eliminate risk, but research suggests they can reduce it substantially. Many infections also come from food, especially undercooked lamb, pork and game, so standard kitchen hygiene still matters.

Key terms that help make sense of the research

Three ideas help clarify the current debate:

- Latency: a state where a pathogen remains in the body without causing obvious symptoms. Toxoplasma was long placed firmly in this category.

- Low-grade inflammation: a persistent, mild activation of the immune system, which has been linked with depression, cognitive decline and heart disease.

- Correlation vs causation: many studies show that toxoplasma carriers and certain conditions tend to appear together. Proving that the parasite directly causes those conditions is far harder.

Researchers now suspect that chronic toxoplasma infection may drive low-grade inflammation in some brains, nudging existing vulnerabilities rather than creating disease from nothing.

How this could play out in real life

Imagine two people with similar genetic risk for depression. One has never had toxoplasma; the other carries chronic cysts. If the parasite amplifies stress responses by even a small margin, the second person might be more likely to develop symptoms under pressure.

On a population level, that kind of subtle push could shape statistics on mental illness, accident rates or even workforce productivity. No single case would conclusively point to a parasite, but the pattern could still be real.

For now, scientists urge balanced attention rather than panic. The new data argue against dismissing toxoplasma as a harmless hitchhiker, yet they stop short of framing it as a hidden catastrophe. The parasite seems less like a silent passenger and more like a long-term, low-level negotiator, constantly bargaining with our immune system and brain cells over space, resources and control.