The engineers were the first to stop talking.

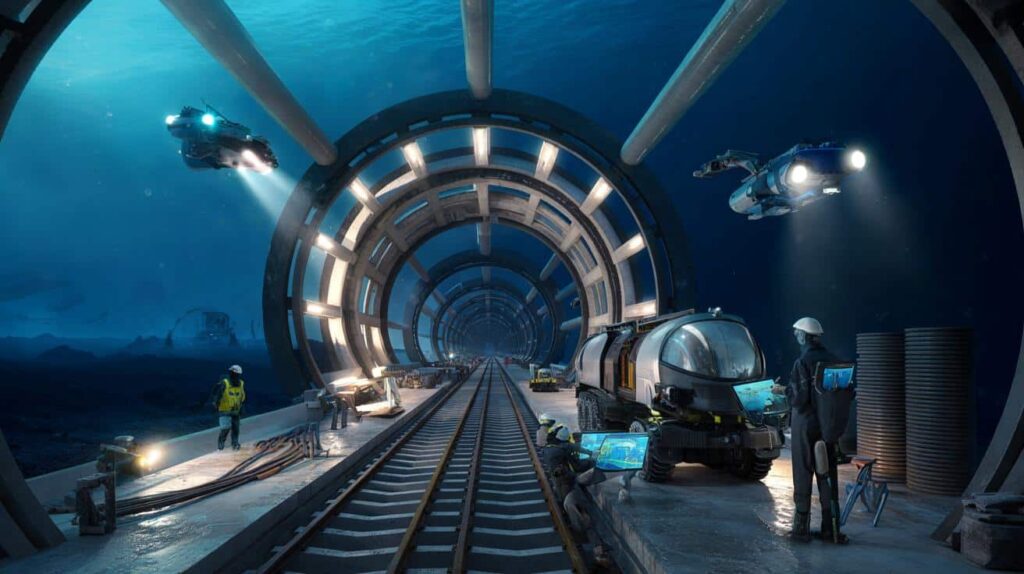

On the deck of a research vessel rocking in the Atlantic swell, a line of orange buoys marked where the future would dive under the waves. A metal cylinder, as high as a house and blunt as a bullet, waited at the stern: the first segment of a rail tunnel that, if everything goes according to plan, will one day let passengers board a train in Europe and step off in North America without ever seeing the sky.

A crane groaned, a drone buzzed overhead, someone yelled for silence as the barge shifted into position.

Nobody on board used the word “impossible” anymore.

They were too busy building it.

France delivers a 500-tonne steel giant to power the UK’s new Hinkley Point C nuclear reactor

France delivers a 500-tonne steel giant to power the UK’s new Hinkley Point C nuclear reactor

From crazy sketch to steel on the seabed

Ask the project’s senior engineer, a woman with salt in her hair and a hard hat tucked under her arm, when she realized this underwater rail line was actually happening, and she doesn’t mention a date.

She talks about a sound.

“The first time you hear the tunnel segment kiss the seabed,” she says, “you understand this is no longer a drawing.”

That “kiss” is a hollow, low thud, as tons of prefabricated steel and composite drop gently into a trench carved in the ocean floor.

For years, this deep-sea tunnel was a billionaire’s fantasy, a Reddit rumor, a sci‑fi backdrop.

Now, the work site stretches like a ghost highway beneath some of the roughest waters on Earth.

Follow the cable cameras down and the scale becomes strange, almost unnerving.

Robot excavators crawl along the seabed, shielded in thick armor, slicing a trench through silt and ancient rock.

Behind them, remotely operated vehicles line up the first tubular segments, each longer than a city block, locking them together with huge hydraulic “hands”.

Every joint is wrapped, tested, then buried again under layers of ballast and protective rock.

It’s not just one tunnel either.

Engineers talk about a clustered spine: parallel pressure-resistant tubes for high-speed trains, companion corridors for maintenance, fiber‑optic cables, and high‑voltage lines piggybacking on the same route to shuttle electricity between continents.

What used to be a wild idea now sits on a spreadsheet full of deadlines.

Costs are measured in the trillions, yes, but so are the economic models: cut transatlantic flight demand by a third, slash shipping times for high-value freight, stitch research hubs together as if they were neighboring suburbs.

The physics are brutal. Pressure at the deepest sections is hundreds of times what you feel at sea level, saltwater eats everything it touches, and minor leaks turn into catastrophic failures if ignored.

That’s why the structure isn’t just heavy; it’s smart.

Sensors baked into the tunnel’s skin listen for micro‑cracks, shifts in temperature, suspicious vibrations from passing quakes.

If something whispers wrong, an alert pings control rooms on two continents at once.

How do you actually build a train line under an ocean?

The method looks surprisingly methodical when you break it down.

Engineers start by mapping every bump and crease of the ocean floor with sonar and autonomous submarines, hunting for faults, unstable slopes, or rogue boulders big as houses.

Next comes dredging, carving a shallow canyon along the chosen route.

On land, giant factories churn out the tunnel segments: double-walled tubes packed with vacuum insulation, shock absorbers, and emergency walkways, each tagged with sensors before it ever sees water.

Once at sea, those segments are floated out, sealed, and gently sunk into the trench, guided by GPS, lasers, and dozens of underwater drones.

The process is maddeningly slow, but that’s the point.

The easiest mistake is to imagine this like laying track across a quiet field.

It’s more like stitching a fragile artery across a living, unpredictable animal.

Storms slam the surface ships, currents shove at anything dangling in the water, and schedules bend around hurricane season, not investor calls.

On one rough morning last autumn, a 400‑meter segment swung just a little too far off course as waves stacked up against the barge.

They paused the whole operation for three days.

You could feel the tension in the emails from shore: satellite time rescheduled, tugboats put on standby, insurance teams asking pointed questions.

Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every single day.

You can be a world‑class engineer and still get a knot in your stomach watching a billion‑dollar tube vanish into black water.

Behind every technical decision sits a quiet, uncomfortable question: what if something goes wrong 4,000 meters down?

Evacuation pods, pressure locks, parallel service tubes – these aren’t movie props, they’re design requirements.

Regulators from multiple countries insisted on thick redundancy: multiple fireproof compartments, independent air and power, rescue “islands” every few kilometers with lifeboat‑like capsules able to surface autonomously.

*If you’re picturing a space station turned horizontal and buried in the seabed, you’re not far off.*

One systems architect put it bluntly:

“We’re building for the worst day this tunnel will ever see, not the best day politicians will cut a ribbon,” he said. “People will forget how complex it is the second they sit down and open their laptop on board. That’s exactly the goal.”

To keep focus, internal documents circle the same simple checklist:

- Protect life first, even if it hurts capacity

- Design for 100+ years, not one generation’s glory

- Assume rising seas and shifting politics

- Collect data from day one, adjust in real time

- Never let routine become complacency

What this deep-sea tunnel quietly changes for the rest of us

Most of us will never stand on that research vessel or peer through those control room windows.

We’ll just see headlines, renderings of sleek train cabins, maybe a 3D animation of the line wrapping the globe like a silver thread.

Yet the logic behind this mega‑project leaks into everyday life.

If continents can be bound by a pressurized tube under crushing water, the mental distance between them shrinks too.

An artist in Lagos pitching a client in São Paulo, a climate scientist coordinating teams in Vancouver and Reykjavik – suddenly, the idea of “far away” feels a little less rigid.

We’ve all been there, that moment when a once‑ridiculous technology suddenly becomes the new normal.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| First deep-sea rail megatunnel | Engineers are already laying prefabricated tubes in a trench on the ocean floor | Understand how a “sci‑fi” concept is turning into a real transport option |

| Smart, sensor‑laden structure | Built‑in monitoring tracks cracks, shifts, and pressure 24/7 across continents | Offers a glimpse of how future infrastructure will quietly watch over our safety |

| New economic and social links | Potential to cut flight demand, move power and data, and pull cities into new alliances | Helps you picture how work, travel, and even identity might shift in your lifetime |

FAQ:

- Will passengers really be able to travel between continents by train?The initial plans focus on freight and maintenance runs, but project leaders say passenger service is part of the long‑term design. Early projections talk about crossing an ocean in under six hours, door to door, including check‑in.

- Is this safer than flying?“Safer” depends on the final safety record, but the tunnel is being designed with multiple layers of protection, fire compartments, escape capsules, and constant sensor monitoring. Long rail tunnels already have strong safety stats; this one borrows heavily from that playbook.

- How deep will the tunnel go?The route snakes to avoid the very deepest trenches, but some sections still sit several thousand meters below the surface. That’s why the structure is laid on the seabed in a protected trench, not suspended halfway down in the open water.

- What about earthquakes and shifting tectonic plates?Engineers have sited the main corridor away from the most active fault lines and built expansion joints and flexible couplings into the structure. The tunnel isn’t rigid from end to end; it’s designed to flex and absorb movement.

- When could ordinary people ride this thing?Timelines shift, and nobody serious promises an exact year, but construction schedules speak in decades, not centuries. The first operational freight corridor could be running before today’s schoolkids hit middle age, which is both distant and strangely close.